Washington State is the United States’ fastest growing, major wine region. The second-largest wine producing state in the union, it grew from 100 wineries to 900 in just 20 years and now tops 1,000. It quintupled vine acreage to 55,000 over the same period. It now makes slightly more wine than the third- and fourth-highest producing states combined (New York and Pennsylvania).

Washington’s growth has come in all price segments. There’s plenty of Washington wine, red and white, under $20. There’s a wealth of tasty wines between $20 and $50. The state has also become known for tremendous, low-volume, high-scoring wines with prices well above $100.

All images courtesy of Washington State Wine

All images courtesy of Washington State Wine

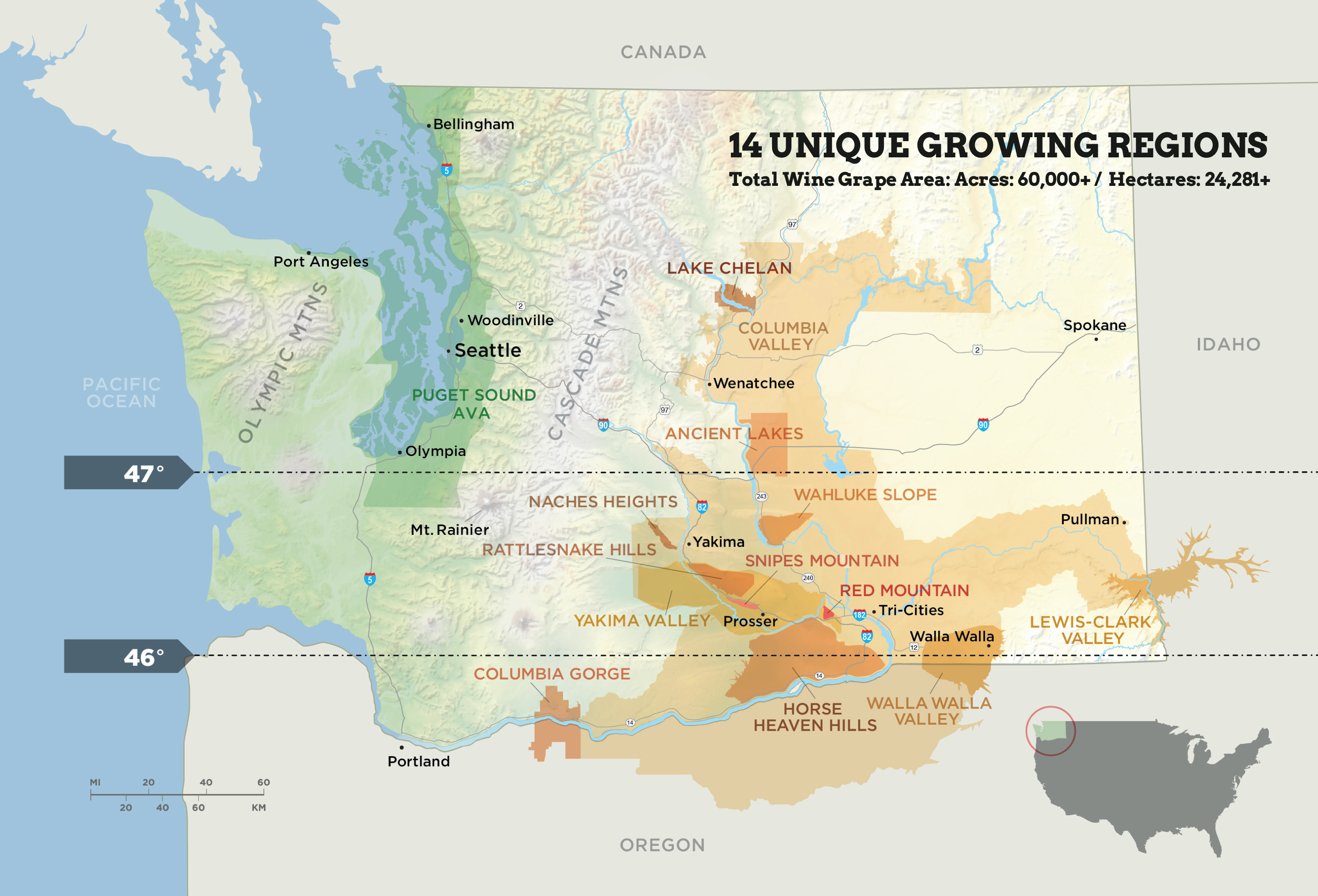

The Geography of Washington State Wine Regions

Washington State is, of course, in the Pacific Northwest. Its southern neighbor is Oregon; Idaho is to the east. Canada’s British Columbia is on the north. The Pacific Ocean bounds Washington on the west.

Due to the proximity of Oregon, a major wine state itself, you might think wines from the two states would be similar. In some cases, they are. But, for the most part, their wines and the regions which make them are dissimilar.

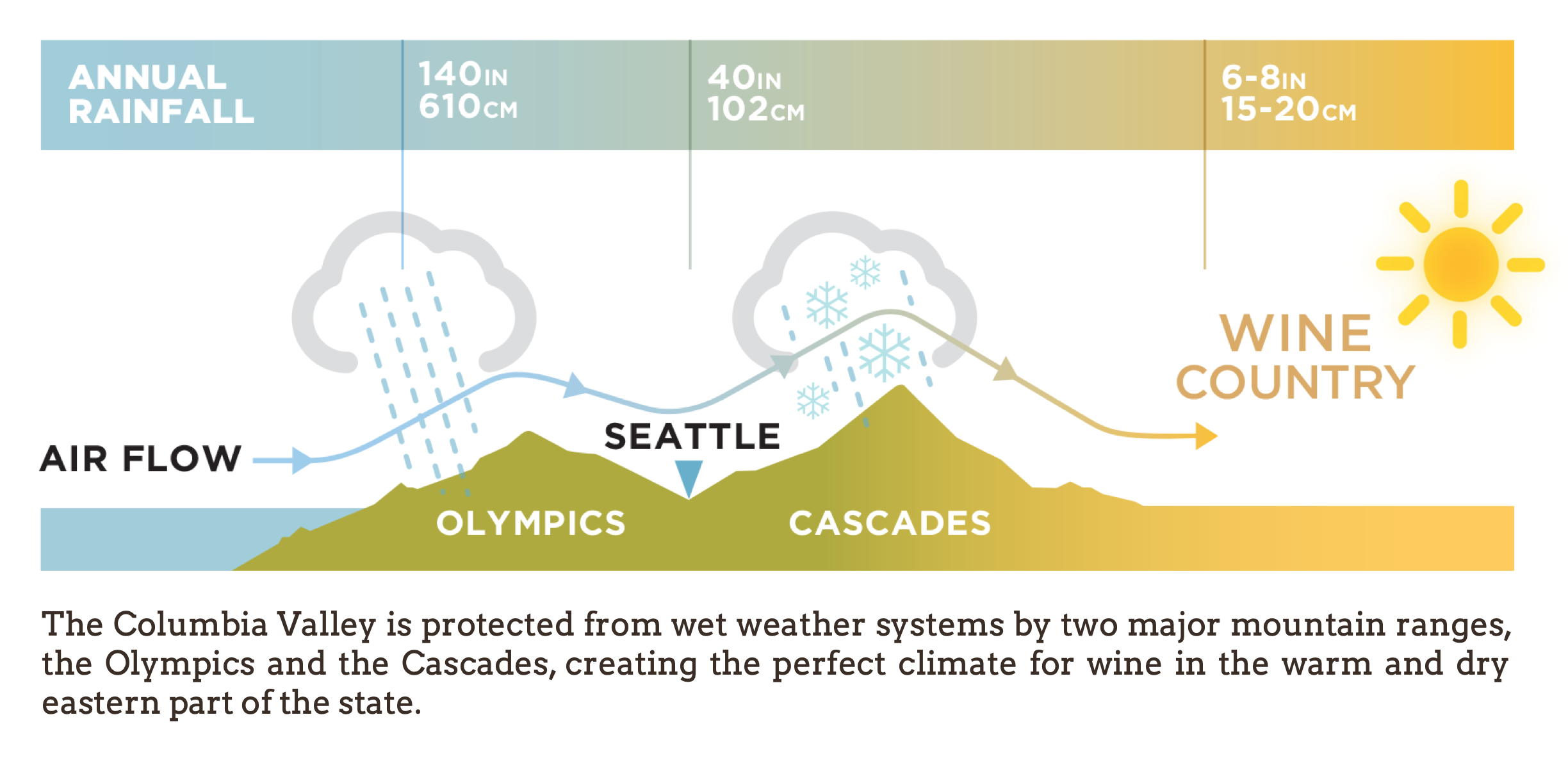

The Cascade Mountains cause the primary difference. This massive mountain range runs north-south through both states. The mountains block the cool air and precipitation that head east from the Pacific. In Oregon, most of the wine regions are west of the Cascades, so they are relatively cool and their rainfall is similar to that of Napa Valley. Almost all Washington wine comes from east of the Cascades, where the growing season is quite warm and there’s very little annual rain.

The soils also differ. Most of Oregon’s vineyard soils are some combination of ancient marine sedimentary, alluvial wash from the mountains, and volcanic. Washington’s soils are newer and dominated by two phenomena: volcanic lava flows and flood waters released as the last Ice Age came to an end.

The lava flows created layers of basalt and granite. They are the bedrock in many vineyards. But, over many thousands of years, that rock was also eroded into sand and fine silt. That blew great distances and eventually settled, forming thick layers of soil called loess. It may seem odd that a deep soil can be created by blowing dust, but think about how quickly blowing sand in the desert can cover vehicles, and even towns.

The Missoula flood soils are named after the location of a massive ice dam that held back a 2,000-foot deep lake. [That’s 33% deeper than the Empire State Building is tall.] As the dam gradually melted it released those waters which ran toward the ocean, flooding everything in its path.

The flood soils are of two basic types: Fastwater and Slackwater. Fastwater soils are big stones and cobbles that could be carried by deep, fast-running water. They’re mostly found in relatively narrow zones that show the raging torrents’ paths. This soil, which can be hundreds of feet deep, is low-fertility and very well draining.

As the rushing water spread out to either side, it got shallower and slower. The less energetic water could only carry small particles of soil. So, Missoula Flood Slackwater soils are broad, deep, multi-layered fields of light sediment. This soil holds much more water than the Fastwater soil (but less than loess). However, there are sometimes layers which are too hard for vine roots to penetrate. That, coupled with the hot, arid climate, means irrigation is often necessary.

The layered Slackwater Missoula Flood soil

The layered Slackwater Missoula Flood soil

Washington State AVAs

Puget Sound AVA

Puget Sound AVA is the only Washington growing region west of the Cascades. It rings the Sound and comprises almost three million total acres, including the Seattle, Woodinville, and Bellingham metro areas. But there are only about 100 acres of vines in the whole area. The climate is cool and maritime. Hybrid varieties do well.

Columbia Gorge AVA

The Columbia Gorge AVA has a transitional climate, straddling the Columbia River where it cuts through the Cascades. But this AVA, which lies in both Washington and Oregon, is also relatively small. And only one-quarter or so of its 1,300 planted acres are in Washington. There are just three wineries on that side of the river.

Columbia Valley AVA

The Columbia Valley AVA is, by far, Washington’s largest. Every AVA in the state, except Puget Sound and Columbia Gorge, is nested within it. It also overlaps part of northeastern Oregon. How big is the AVA? It is 11 million total acres, larger than the entire country of Denmark.

The portion of the Columbia Valley AVA that lies in Washington is 8,748,949 acres, upwards of 56,000 planted. 99% of all Washington State wine comes from the Columbia Valley AVA. Yet, to put things in perspective, that’s only half as many planted acres as you’ll find in California’s Lodi AVA. And, though Washington has the second-highest wine production of all states, its volume is only 6% as much as California’s.

Columbia Valley AVA Climate

Because the Columbia Valley is so large, it has many mesoclimates. However, the overall climate is continental, since there’s no oceanic influence. It’s very dry and warm during the growing season, cold during the winter. Total annual precipitation averages eight inches or so, most coming during winter and early spring.

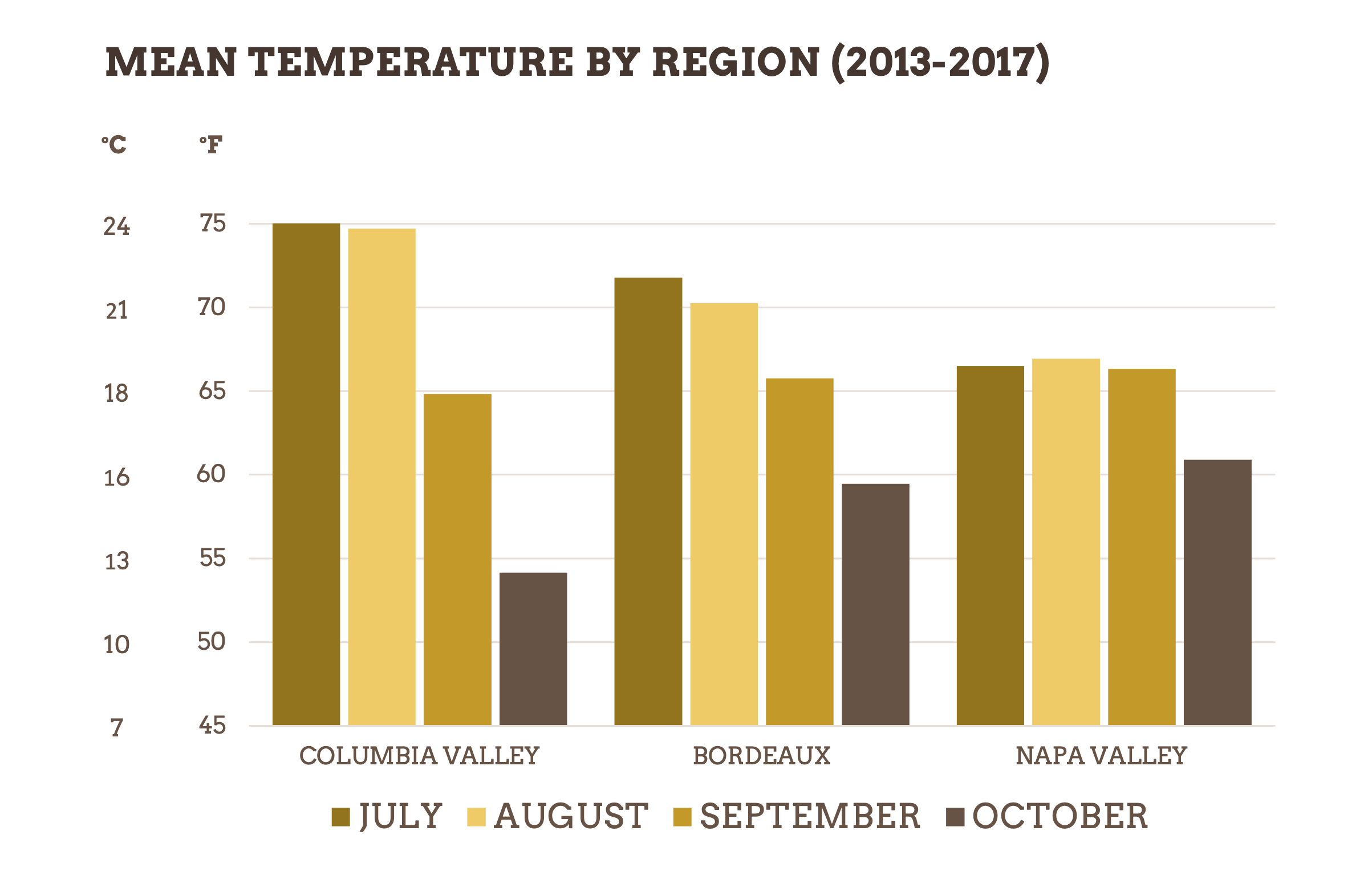

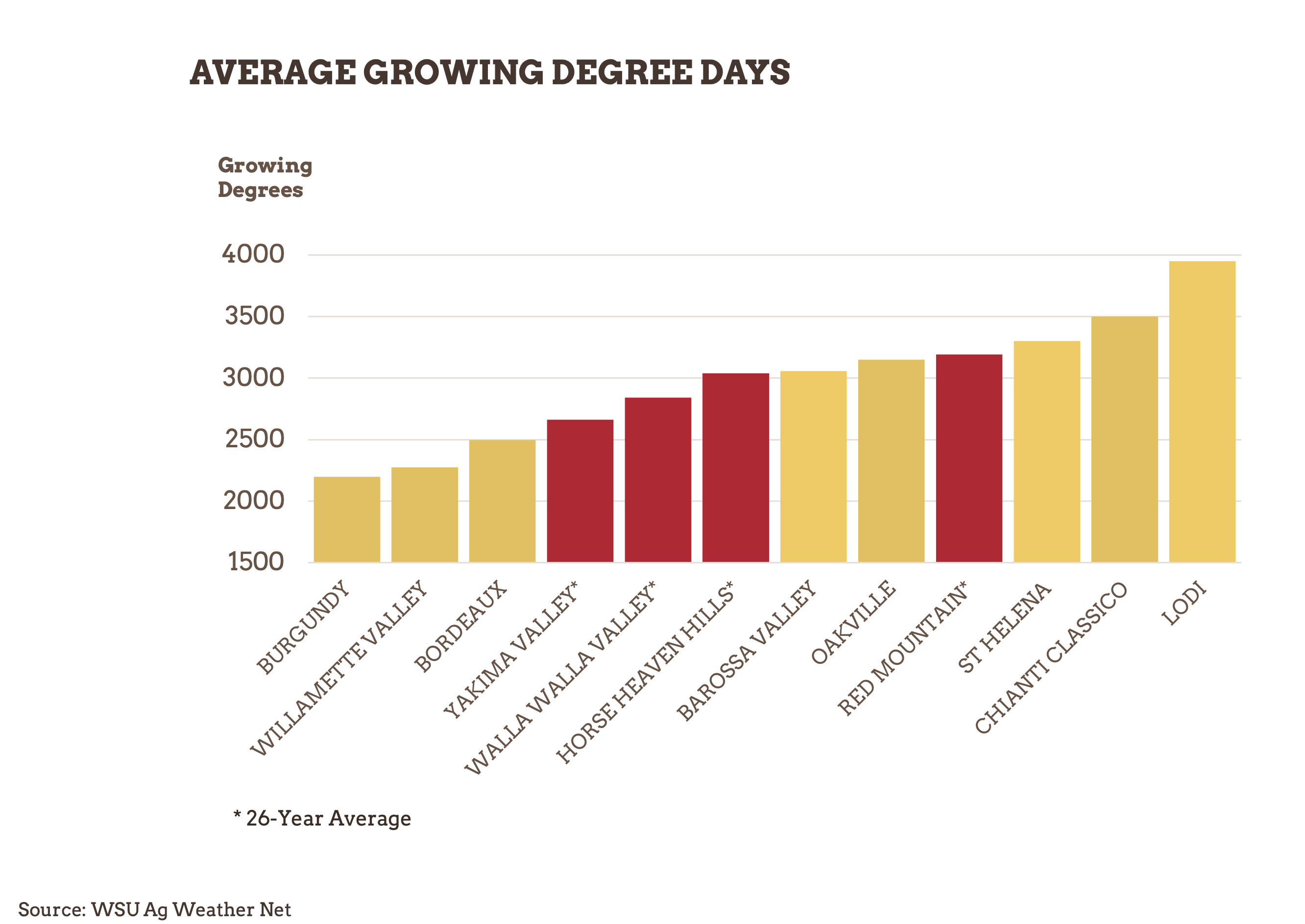

The growing season runs 180-200 days, depending on the grape variety, specific location, and year. That’s about the same as in Napa Valley and Bordeaux. However, the dynamics of those growing seasons are quite different.

Bordeaux has a maritime climate and thus experiences a lot of cloud cover and rainfall throughout the growing season. Columbia Valley and Napa get neither.

Columbia Valley (46-47° latitude) is much further north than Napa Valley (38°), so the Washington vineyards get an hour more daily sunlight during the heart of the growing season. But, the days are shorter than Napa’s at both ends. Bordeaux (45°) is similar to Columbia Valley in this respect, though the sun is moderated by clouds.

The combination of dry, sunny weather, a lengthy growing season, and long mid-season days gives Columbia Valley excellent ripening potential for moderately robust red varieties, such as those from Bordeaux, Spain, and the Rhone Valley.

Walla Walla Valley AVA

Nested within the southeastern portion of the Columbia Valley AVA, the Walla Walla Valley AVA also overlaps Oregon. The Washington side has fewer acres under vine, 1,700 vs. 3,000. However, because Washington’s town of Walla Walla is the AVA’s biggest, there are a lot more wineries on the Washington side. This overlap can cause some labeling confusion when most of the grapes come from Oregon and the wine is made in Washington. Clarifying legislation is underway.

The Walla Walla Valley AVA includes all of Columbia Valley’s key soil types: volcanic, loess, and both Slackwater and Fastwater Missoula Flood deposits. The combination of soils and climate make the area especially good for Syrah. Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache can also be stellar.

Horse Heaven Hills AVA

Horse Heaven Hills is directly west of the Walla Walla Valley AVA. The two are separated by a bit of land and the southernmost extent of Columbia River’s north-south run. Horse Heaven Hills’ southern border is also the Columbia River, so the AVA lies entirely in Washington State. Its northern border is the Yakima Valley AVA.

This AVA is 576,603 total acres overall, with more than 17,000 planted. It produces 25% of Washington’s wine. The soils of loess and Missoula Flood receive very little rain, making irrigation imperative. Despite benefitting from winds running through the Columbia River valley, predominantly southern facings make this one of Washington’s warmest AVAs.

66% of its vines are red wine varieties. Among white wines, Riesling is arguably the best. The first, second, and third Washington wines to receive 100-point scores came from Horse Heaven Hills.

Yakima Valley AVA

Established in 1983, Yakima Valley was the first AVA in the Pacific Northwest. It’s nearly 19,000 planted acres include more than one-third of the state’s vineyards. The soils are predominantly fairly well-draining Slackwater Missoula Flood. Like its neighboring AVAs, the climate is quite warm and rainfall scant. Irrigation is essential.

Yakima Valley AVA has more diversity in facings than Horse Heaven Hills. That, and being further north, makes some of its zones cooler. Consequently, there’s a more even balance of white to red varieties. In fact, more than 50% of the state’s Chardonnay and Riesling come from Yakima Valley.

Rattlesnake Hills AVA

This AVA is nested within the north-central portion of the Yakima Valley AVA. With an elevation of 850-3,085 feet, Rattlesnake Hills is the highest zone within Yakima Valley. Most of the 1,800+ planted acres are in the low altitudes. Nonetheless, they are high enough that risk of frost is lower and average daily temperatures higher. Vineyard soils are predominantly Missoula Flood, but the highest areas remained above the floodwaters. The red-white mix is about 50-50 and the primary grapes Riesling, Merlot, and Cabernet Sauvignon.

Snipes Mountain AVA

The second smallest AVA in Washington, Snipes Mountain is also nested within Yakima Valley. It’s a 4,005-acre sliver of land sandwiched between southeastern Rattlesnake Hills to the north and the Yakima River on the south. More of a slope than a mountain, its 820 planted acres are on particularly infertile Slackwater and Fastwater Missoula Flood soils. The main grapes are Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon, but 30 varieties are grown.

Red Mountain AVA

Nested in the far eastern corner of the Yakima Valley AVA, Red Mountain runs steeply from 500 feet to 1,500. The southwest facing overlooks the Yakima River. It’s perhaps the most densely planted of all Washington AVAs, roughly half of its 4,538 total acres are under vine.

Red Mountain is one of the driest Washington AVAs. It’s also the hottest, though it does benefit from an extreme diurnal shift. Soils are very low in organic materials and the mineral makeup also limits vigor. All these factors, plus swift, desiccating winds lead to notably tannic Cabernet Sauvignon. The most noteworthy white variety is Sauvignon Blanc.

Wahluke Slope AVA

A broad, shallow, south-facing slope from 1,480 feet down to 425, Wahluke Slope has the most homogenous terroir of Washington’s AVAs. Most of the roughly 9,000 acres are planted in the lower half on an alluvial fan blanketed deeply by loess. One of the warmest AVAs, most vines are red varieties, though there is Riesling, Chardonnay, and Chenin Blanc. Syrah is the signature red variety with Cabernet Sauvignon a close second.

Naches Heights AVA

Only 35 acres vines reside in this high altitude AVA. The long, thin region angles northwest from the town of Yakima. A minimum altitude of 1,200 feet puts it above all Missoula Flood soils. Instead, the soil is deep, clay-rich loess on top of volcanic flow. Relatively cool weather and the water-retaining soils mean irrigation isn’t always necessary and white wine grapes do well.

Ancient Lakes AVA

Ancient Lakes is second-furthest north among Columbia Valley’s nested AVAs. The Columbia River on its western border moderates temperatures and limits frost, but the northern latitude still results in a relatively short growing season. That, in turn, means fewer degree days and a fairly cool climate by Washington’s standards. White wine varieties dominate the 1,600 planted acres and Riesling is king among them.

Lake Chelan AVA

By far the northernmost AVA nested within Columbia Valley, this AVA is bisected by the lake after which it’s named. The lake—55 miles by one mile—and the land have almost identical total acreage, just over 24,000 each. Planted acres are only about 250 though. Situated north of the the Missoula Floods’ path, soils are glacial sediment, volcanic ash and pumice. Twenty grape varieties grow there with no consensus yet on which is best.

Lewis-Clark Valley AVA

This AVA is in the easternmost portion of Columbia Valley, but most of it lies in Idaho. Its climate is moderate and good for viticulture. However, only nine acres of vines are planted on the Washington side.

Conclusion

Washington State is the United States’ second largest wine producer. Its AVAs cover vast areas, but most of the growing is focused in specific places. The predominantly warm, dry growing season can accommodate a wide range of grape varieties, though its best, high-volume wines tend to be Bordeaux- and Rhone-variety reds, along with Riesling and Chardonnay. Enjoy a bottle while musing about how epic those Missoula floods must have been.

JJ Buckley has a nice selection of Washington State wines. Here are some examples which are among the best Washington wines made.

2016 Charles Smith Royal City Stoneridge Vineyard Syrah

2016 Quilceda Creek Cabernet Sauvignon

2017 Leonetti Cellar Cabernet Sauvignon

2013 Delille Cellars Grand Ciel

2016 K Vintners El Jefe Stoneridge Tempranillo

JJ Buckley guest blogger Fred Swan is a San Francisco-based wine writer, and educator. His writing has appeared in The Tasting Panel, SOMM Journal, GuildSomm.com, Daily.SevenFifty.com, PlanetGrape.com, and his own site, FredSwan.Wine (formerly NorCalWine) among others. He teaches at the San Francisco Wine School. Fred is founder of Wine Writers' Educational Tours, an annual, educational conference for professional wine writers. He also leads private wine tours and conducts tastings and seminars in person and via Zoom. Fred’s certifications include WSET Diploma, Certified Sommelier, California Wine Appellation Specialist, Certified Specialist of Wine, French Wine Scholar, Italian Wine Professional, Napa Valley Wine Educator, Northwest Wine Appellation Specialist, and Level 3 WSET Educator. He's been awarded a fellowship by the Symposium for Professional Wine Writers three times.